When I was a kid, I didn’t grow up with Pokémon. No trading cards, no cable TV showing Pikachu adventures — just a distant idea that somewhere in the world, people were obsessed with catching imaginary creatures.

Years later, when I saw people paying thousands of dollars for a single piece of paper — a Pokémon card — I thought, “Are they crazy?”

But the deeper I looked, the more I realized it wasn’t crazy at all. It was marketing genius.

The Humble Beginning

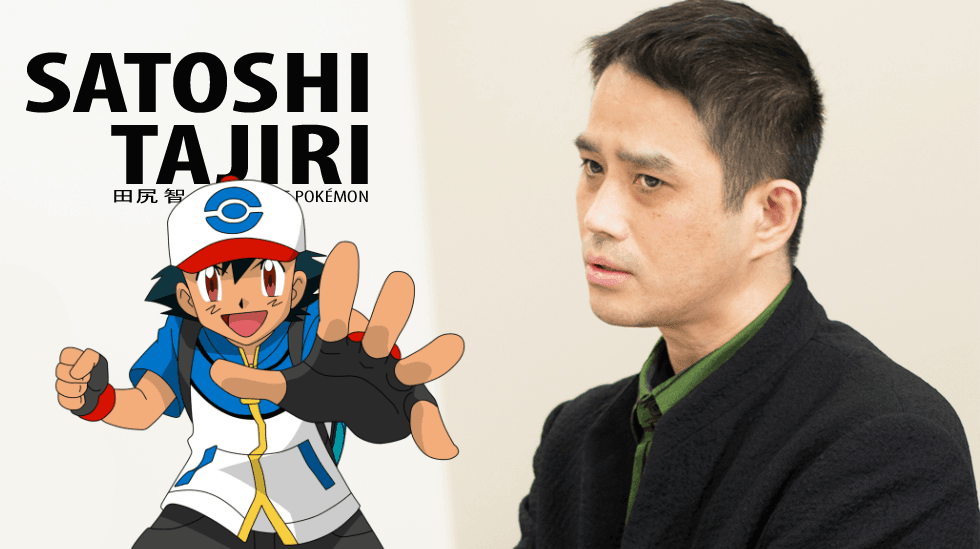

Pokémon started with one man’s childhood obsession.

Satoshi Tajiri, a boy from Japan in the 1970s, loved exploring the outdoors, collecting insects, and trading them with friends. He noticed that modern city kids didn’t have that kind of freedom or adventure. He dreamed of recreating that thrill in a game.

It took years of grind to make that dream real. Tajiri started Game Freak as a magazine about video games, teaching himself and his team the skills to develop a full-fledged game. Nintendo saw potential but also risk: Tajiri was young, inexperienced, and the Game Boy was already struggling with a crowded game market.

Yet, Tajiri persisted. After countless setbacks — design challenges, hardware limitations, and financial risk — Pokémon Red and Green launched in 1996.

And it worked.

The game’s magical hook was social interaction. You couldn’t catch ’em all alone — trading with friends via link cables was essential. Suddenly, a simple game became a shared adventure.

The Perfect Ecosystem

From the start, Pokémon wasn’t designed to be just one product — it was a world.

Nintendo launched three things almost together:

- The video game, where players collected and trained Pokémon.

- The anime, where kids followed Ash and Pikachu on emotional adventures.

- The trading card game, where players could hold a piece of that world in their hands.

Each part fueled the other. The anime made you love the characters. The game made you want to collect them. The cards let you show that love to others.

It was a self-feeding cycle — a marketing ecosystem disguised as fun. Pokémon wasn’t a single product. It was a whole universe, with fans living in it.

The Psychology Behind the Craze

The brilliance of Pokémon lies in how it connects with human instincts:

- The urge to collect – That thrill of finding something rare.

- The joy of belonging – Trading with friends, being part of a community.

- The emotion of nostalgia – Remembering the simpler, happier times.

Pokémon didn’t just sell entertainment. It sold feelings.

It created an emotional economy where cardboard and digital creatures carried meaning far beyond their physical worth.

And here’s the genius: Pokémon never rushed to change everything.

Each new generation of games introduced new creatures but kept the same spirit — “Gotta catch ’em all.” That consistency built decades of trust and nostalgia.

How They Kept It Relevant

You’d think a 1990s franchise would fade out, but Pokémon did the opposite.

When smartphones took over, they released Pokémon GO in 2016 — an augmented-reality game that made people actually go outside to “catch” Pokémon in real places. Suddenly, cities were full of people walking around with their phones, chasing virtual creatures.

It was madness — and marketing magic.

Pokémon had managed to connect a new generation through the same spirit of exploration that Tajiri dreamed about as a kid.

That’s not luck — that’s adaptation without losing identity.

The Art of Selling Meaning

Here’s what I find most fascinating: Pokémon sells meaning, not material.

A shiny card may cost a few cents to print, but it represents childhood memories, competition, community, and pride. When collectors spend thousands, they’re not buying paper — they’re buying identity.

It’s the same psychology luxury brands use, but Pokémon does it with innocence and imagination.

And for marketers, that’s a gold lesson:

People don’t buy products. They buy the stories they tell themselves through those products.

What We Can Learn

From a marketing lens, Pokémon’s success isn’t just about nostalgia — it’s about building an emotional ecosystemwhere every product reinforces the other.

- Keep your core story consistent, even as you evolve.

- Create products that connect people, not just entertain them.

- Let your audience feel ownership — whether that’s through collecting, sharing, or creating.

- And never underestimate emotion — it scales further than any advertising budget.

Final Thoughts

I might not have grown up with Pokémon, but studying it feels like discovering a rare card of my own — a hidden lesson in how storytelling and psychology can turn a simple idea into a global phenomenon.

Pokémon didn’t just teach kids to catch monsters.

It taught marketers how to capture hearts.

Shain Studio

Shain Studio

Comments

Comments feature coming soon! In the meantime, feel free to reach out via the contact page.